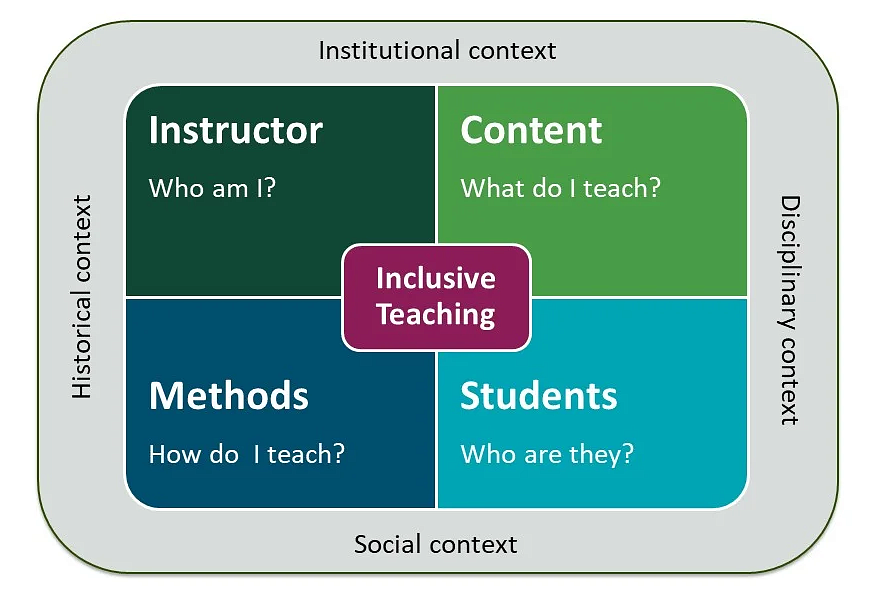

Inclusive teaching strives to engage and value every student and attend to the social and emotional climate of the class. Inclusion is enacted through particular choices faculty make in their presentation of self and content, and through deliberate ways of drawing on assets each student brings to the classroom. The philosophy and practices of inclusive teaching apply to all UO faculty and all UO courses, regardless of faculty discipline or course content.

At the University of Oregon, inclusive teaching is one of the four criteria for teaching standards. For the purposes of our practice and teaching evaluation, inclusive teaching standards are defined as teaching in which:

- Instruction designed to ensure every student can participate fully and that their presence and participation is valued.

- The content of the course reflects the diversity of the field's practitioners, the contested and evolving status of knowledge, the value of academic questions beyond the academy and of lived experience as evidence, and/or other efforts to help students see themselves in the work of the course.