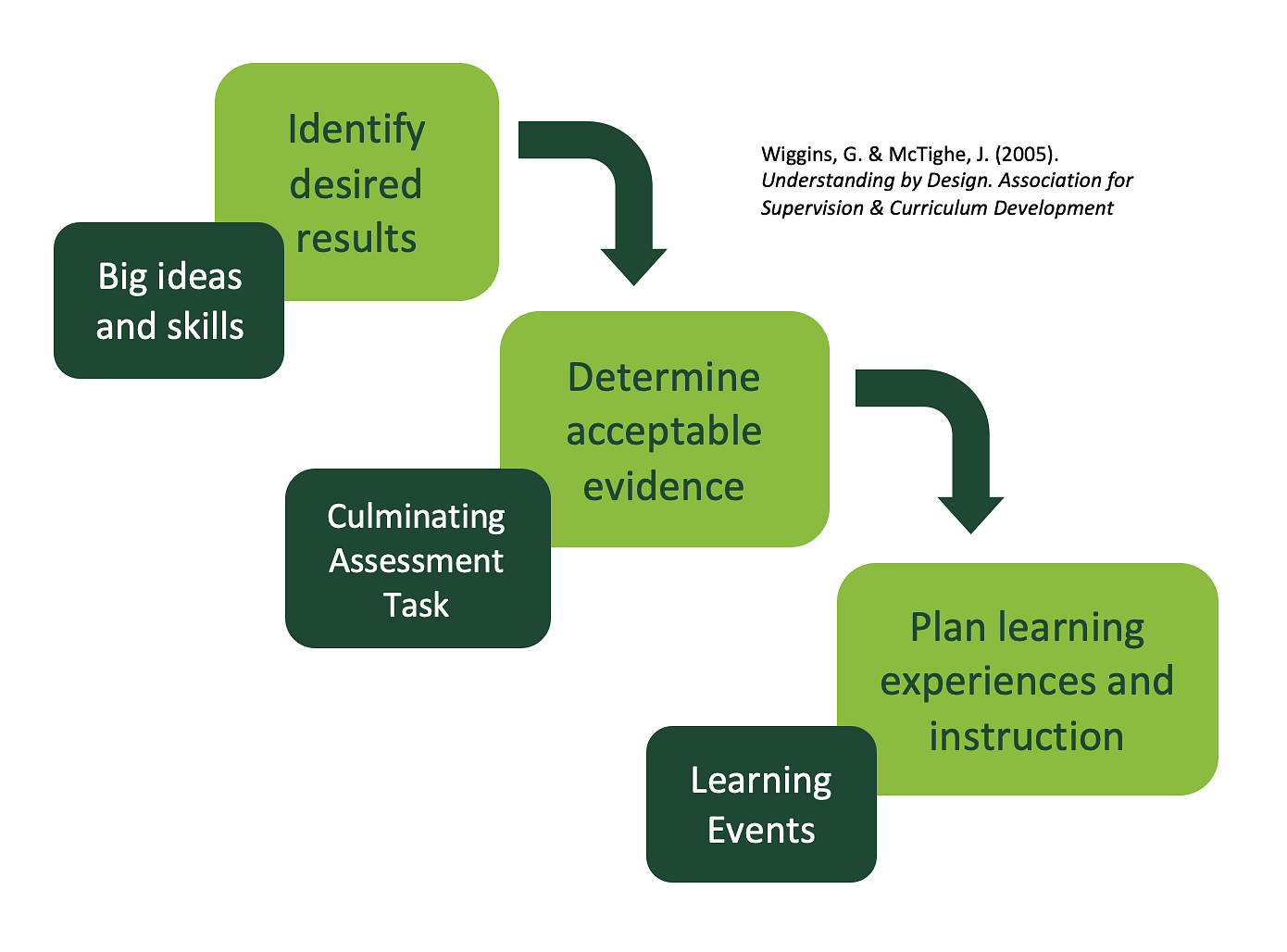

When we talk about "aligned design" we're often referring to the Backward Design process, a term coined by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe in their book Understanding by Design (2nd Ed., 2005). They describe the three stages of the process:

- Identify desired results

What should students know and be able to do at the end of the course? These are your learning objectives.

Guiding Questions

- What are the established goals?

- What "big ideas" do we want students to come to understand?

- What essential questions will stimulate inquiry?

- What knowledge and skills need to be acquired given the understandings and related content standards?

- What focus questions will guide students to targeted knowledge and skills?

- Determine acceptable evidence

How do you know that students have achieved the learning objectives? These are your formative and summative assessments.

Guiding Questions

- What is sufficient and telling evidence of understanding?

- Keeping the goals in mind, what performance tasks should anchor and focus the unit?

- What criteria will be used to assess the work?

- Will the assessment reveal and distinguish those who really understand versus those who only seem to understand?

- Plan learning experiences, instruction, and resources

What will help students be able to provide evidence that they have met the learning objectives? These are your instructional materials, learning experiences, and general course content/resources.

Guiding Question

What instructional strategies and learning activities are needed to achieve the results identified in the outcomes and reflected in the assessment evidence?

TEP’s backward design handout can help you get started writing learning objectives and aligning them with the work of the course.